Xibolai. The seminary student was using it a lot and I felt pleased I could translate my favorite Chinese word. It means "Israelite" and sounded remarkably like my favorite Hebrew word—Shibboleth. You may have heard the word shibboleth. In modern usage, it refers to an entrenched belief or custom that defines a culture. Depending on how you pronounced it in Hebrew three thousand years ago (it meant growth or flow), well, it could have you killed.

The book of Judges tells the complex story of inter-tribal conflict between the outlaw Jepthah of Gilead and the men of Ephraim (all of them Israelites) that led to land grabbing and warfare. When the men of Ephraim tried to cross back into their land, the men of Gilead would force them to say the word Shibboleth. If they said Sibboleth (an ear of corn), there was no mercy.

Unfortunately, Xibolai (希伯来语) was one of only ten words I could translate during the sermon. So, for lack of anything else to do, I began computing. This July 4th weekend marks the sixth anniversary since I returned from a three year teaching stint in China. If I had continued my language studies and learned just one Chinese character per day, I would be literate in Chinese. If I continued learning at that pace for the next three years…. Look at it this way: a scholar knows at least 5,000 of the 10,000+ unique characters in the language and based on my computations, I’d be downright scholarly.

Sunday afternoon, I dusted off my language books and methodically penned the calligraphic strokes of my first word: nü (tone 3), which means woman, girl, daughter. I was so impressed with my ability that I decided to move on to zi (tone 3), which means infant; child; son. My calligraphy looked good to me and I moved on. The next word was hao (tone 3), which means good; right; excellent. Interesting, at least to my eye anyway, was that the composition of this character combined the strokes for woman and son to form the character for “good.” Hmmm. Turning the page, I rediscovered the word for peace, which is: an (tone 1). This character placed the strokes for “woman” under the strokes for “roof.”

Brad walked in about this time and I showed him my resurrected skills. He was my informal language coach in China and he used to shower me with kisses whenever I did well. I’m not sure why we quit our lessons, but I do remember being thoroughly frustrated by the tonality of the language. After a few serious faux pas, such as encouraging people to “eat night soil” instead of “eat more food,” I gave up. Kisses or no kisses, it was easier to communicate in English.

I mentioned my observation of the characters and how they reflected the shibboleths of the culture. If a son with a wife means “good,” and a wife under a roof means “peace,” then what would be two girls and a wife under a roof? My challenge was meant as a rhetorical question, a prompt for cheese that might elicit a witty answer like “love” or “happiness.” He looked at me for a brief moment and in his eyes shone the telling signs that I had made another classic faux pas. My husband exhaled (had he been holding his breath?) “It’s the word for adultery,” he said. “Don’t go trying to make up words in Chinese. It can’t be done. But you’ve done a very good job writing your characters.” And he kissed me.

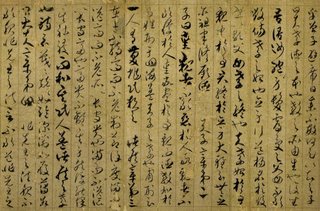

(calligraphy work by He Zhizhang, Tang Dynasty poet)